New Light on Hazel Larsen Archer

“ … Fame's Boys and Girls, who never die/And are too seldom born"

Emily Dickinson in 1865

There’s a mystery that lies at the heart of fame and success in the world, and artists, no less than the rest of humankind, are subject to its whims. Many artists don’t find audience in their own eras, and finish their lives toiling away in obscurity; for them, good fortune means simply being able to continue their work and leave a legacy to the future. Others do find success, wealth, and fame in their own times. What makes the difference? It’s a puzzle. Are those who do not find conventional success simply working so far in advance of the formal and perceptual conventions of their eras that their works cannot be seen clearly by their contemporaries? Certainly the quality of their work, however that might be defined, isn’t the sole variable in the calculus of outcome. Van Gogh, famously, didn’t sell a painting in his lifetime. Friday two weeks ago, March 17th, was the anniversary of the opening of the 1901 show at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery in Paris that made Van Gogh's work famous. Van Gogh, unfortunately, had committed suicide eleven years earlier, never knowing the impact his work would have on painters to come. Lady Luck, the ancient goddess Fortuna, sometimes has a wicked sense of humor.

Black Mountain College, for almost a quarter century a local cauldron of innovation in the arts, produced, of course, artists who renewed (as we can now see) the languages of the visual arts in their era – and often invented whole new tongues. Some of them also became successful in the world. Some did not (or haven’t yet, I want to say, as the youngest of them sail through their seventies), though they did what they could to that end. Some seem to have chosen to focus on other pursuits, having, perhaps, dismissed their own work as artists as insignificant because it did not generate the response that work by their peers received, or having realized that it would take another generation’s eyes to appreciate what they’d attempted.

Of the several remarkable photographers who taught at the college, most have now, fifty years after the college closed, achieved some substantial recognition, at least from their peers. Harry Callahan, to my eyes one of the very great artists of the camera, is perhaps the best known, though even for him success as an artist in the world (as opposed to the darkroom and classroom) came late in life.

One unheralded exception, her work still lost in obscurity, would be Hazel Larsen Archer.

Until, that is, now.

Hazel-Frieda Larsen came to the college from Wisconsin in the summer of 1944, and returned in 1945 to study with Josef Albers; during her years there she also studied with Buckminster Fuller, Robert Motherwell, Walter Gropius, and the photographers Beaumont and Nancy Newhall – this was, after all, the amazing Black Mountain College. After graduation, she joined the faculty, and became the school’s first full-time teacher of photography in 1949, partly, as David Vaughan notes in his soon-to-be published essay on Archer, because of her work during the summer program of 1948. That was a remarkable summer, even for Black Mountain:

John Cage taught music; Merce Cunningham dance; Buckminster Fuller architecture. Willem and Elaine de Kooning were invited at Cage’s suggestion. (Although de Kooning had recently had his first one-man show at the Egan Gallery in New York, they were glad to go because they had been evicted from their apartment.) Richard Lippold was sculptor in residence; his wife, the dancer Louise Lippold was with him and studied with Cunningham. Ray Johnson and Arthur Penn were among the students.

Larsen made photographic studies of Cunningham’s motion in dance, and made portraits as well of Cunningham, Cage, and Johnson. Other of her subjects included Josef and Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, the de Koonings, Fuller, Charles Olson, and Dorothea Rockburne. Later she also photographed Robert Rauschenberg and his wife Sue Weil.

The motion studies are particularly striking. Cunningham, as Vaughan says,

improvised movement as she took the pictures: he remembers that it was difficult because Larsen was very close to him—she was a victim of polio and was confined to a wheelchair, so that she remained stationary while he moved.

Photographing dance is challenging, because the dancer’s movement can cause blurring if the light doesn’t permit very fast shutter speeds – and Larsen was working long before fast multi-coated lenses were available. Many photographers attempt to make a virtue of necessity and use blur to suggest the dance’s motion. Larsen, though, apparently wanted to capture Cunningham’s motion as the eye sees it, and we don’t see blurs unless the motion is mechanically fast, like the turning of a car wheel. Master of timing and eye that she was, she was somehow able to produce images that are clear, the motion beautifully arrested in all its abstract animal glory.

She also, during her years at the college, made photos of trees, leaves, grass, the doors of the “Quiet House” at the College (a small building for meditation), a nearby Baptist church and its graveyard, and other features she discovered in her world.

Larsen left the college in 1953, as its longstanding financial problems began to overwhelm it, and married Charles Archer, who was a student there. They continued to live for several years in the town of Black Mountain, where she opened a studio and took mostly family portraits. In 1956, the year the college closed, she and her husband moved to Tucson, Arizona; she lived there until 1975, when she moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Though her work had been shown at the Museum of Modern Art and the Photo League in New York, she stopped exhibiting after 1957; she focused for the rest of her life on her work as an educator. She died in 2001.

Fortunately, her daughter Erika Zarow preserved much of her work, and it is now scheduled to see the light of day once again. On April 21st the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center will celebrate her creative achievement both by publishing the first extensive collection of her work, and by opening a show in its gallery that will feature many of the book’s images, including some of the motion studies of Cunningham. The book, Hazel Larsen Archer/Black Mountain College Photographer, publishes over a hundred of her photographs, some incorporated in the interpretive text (the essay by Vaughan I’ve quoted from above is part of it), others as full-page duotone reproductions. As those who know me will attest, I’m nuts about books, and this is a handsome book. Alice Sebrell, Project Coordinator for the book (and a gifted photographer in her own right), is enthusiastic about it and the role she thinks it might play:

Since its inception, the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center has

tried to publish and exhibit the work of some of the college's undeservedly under-appreciated artists, in addition to that of the well known and the famous. To focus only on the already famous would misrepresent the true nature of Black Mountain College.

Hazel Larsen Archer's photography is going to astonish people! It's very, very good, and we are really pleased to be able to publish this collection of her work, so the images can be seen and enjoyed by people all over the world. It's a book that will be appreciated by lovers of photography and by people who are interested in Black Mountain College.

Dame Fortuna permitting, the book should do much to lift this gifted photographer from her undeserved obscurity.

The night before, April 20th, you might want to catch the symposium on Black Mountain College being offered at 7:00 PM by the Asheville Art Museum. It brings to town some really notable Black Mountain College scholars, including Mary Emma Harris, author of the wonderful The Arts at Black Mountain College, which is available again in paperback. Her fine Black Mountain College Project website provides historical material on the college, information on some of its faculty and students, a few memoirs, and other resources. The afternoon of the Archer opening, she’ll lead a tour of the college campus, now Camp Rockmont; call the Center at 350-8484 for more information.

********************************

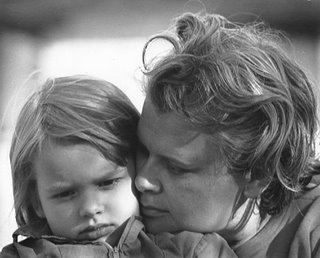

The photo by Hazel captures Hazel and her daughter Erika; date unknown. The print is by Alice Sebrell. There are additional photos by Hazel Larsen Archer, printed by Alice Sebrell, at NatureS

3 Comments:

I can't believe anyone knows who these people are, I remember Erika and her son and Hazel, they were friends of my fathers, he went to Black Mountain, Carroll Warner Williams, I am trying to find out more about him , please contact me if you can

Hi, Beleaguer, You might want to get in touch with Alice Sebrell at the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center in Asheville. Try bmcmac@bellsouth.net

I am one of Carroll’s remaining children. Please don’t hesitate to contact me directly as I remember Hazel very well (and her family), and am always searching for more info related to my father - just as happy to share as well. Contact@caitlanwilliams.com or Caitlan.williams@gmail.com

Post a Comment

<< Home